Southeast Asia’s multi-billion dollar scam industry is facing unprecedented pressure as authorities across the region launch coordinated crackdowns on compounds where hundreds of thousands are forced to perpetrate online fraud. Recent months have seen massive raids in Myanmar, Cambodia and Thailand, exposing the brutal reality of these operations while highlighting the human trafficking crisis that powers what has become the region’s fastest-growing criminal enterprise.

Key Takeaways

- Southeast Asian scam centers generate $63.9 billion annually, with over 305,000 people forced to operate them

- Recent coordinated raids have rescued thousands of victims across Myanmar, Cambodia, and Thailand

- Workers endure brutal conditions including 18-hour shifts, torture, and starvation to meet daily fraud quotas

- Criminal networks continually relocate operations when faced with enforcement pressure

- Regional governance gaps and corruption complicate efforts to permanently dismantle these networks

Multi-Billion Dollar Criminal Networks Face Unprecedented Pressure

The scale of Southeast Asia’s cyber scam industry is staggering, generating $63.9 billion annually with regional operations contributing $39 billion—a whopping 61% of the global total. This criminal empire relies on a workforce of over 305,000 individuals who have been trafficked and forced to operate scam centers across Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand.

These operations emerged from the collapsed casino and tourism infrastructure during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Chinese-led criminal networks saw an opportunity to transform gambling hubs into online fraud factories. The United Nations estimates more than 200,000 people have been trafficked into these centers from at least 66 countries worldwide, creating a human rights crisis that spans continents.

Massive Multinational Enforcement Actions Sweep the Region

Recent months have seen unprecedented cooperation between regional authorities targeting these criminal networks. Along the Thai-Cambodia border, operations led to the arrest of 100 Thai nationals and two Chinese ringleaders in Poipet in March 2025. Even more significant was the rescue of approximately 7,000 foreign nationals—mostly Chinese—from Myanmar’s Myawaddy district between February and March 2025.

Thai authorities have taken the dramatic step of cutting electricity, fuel, and internet to border regions housing scam compounds, aiming to disrupt their operations. This follows earlier actions in late 2023, when militia raids in Myanmar led to the repatriation of over 40,000 Chinese citizens. A joint China-Thailand-Myanmar taskforce further repatriated 600 Chinese workers in February 2025.

These enforcement efforts intensified dramatically after the January 2025 kidnapping of Chinese actor Wang Xing, which brought renewed international attention to the region’s human trafficking crisis and prompted Beijing to put additional pressure on neighboring countries to act.

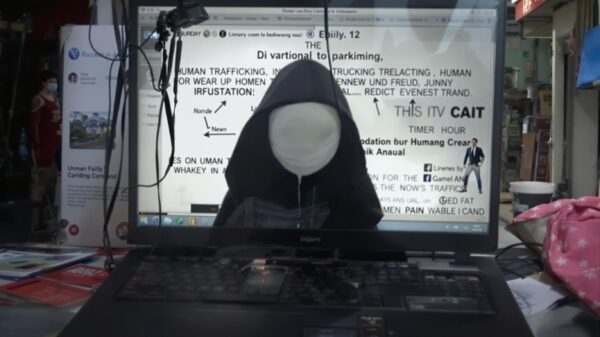

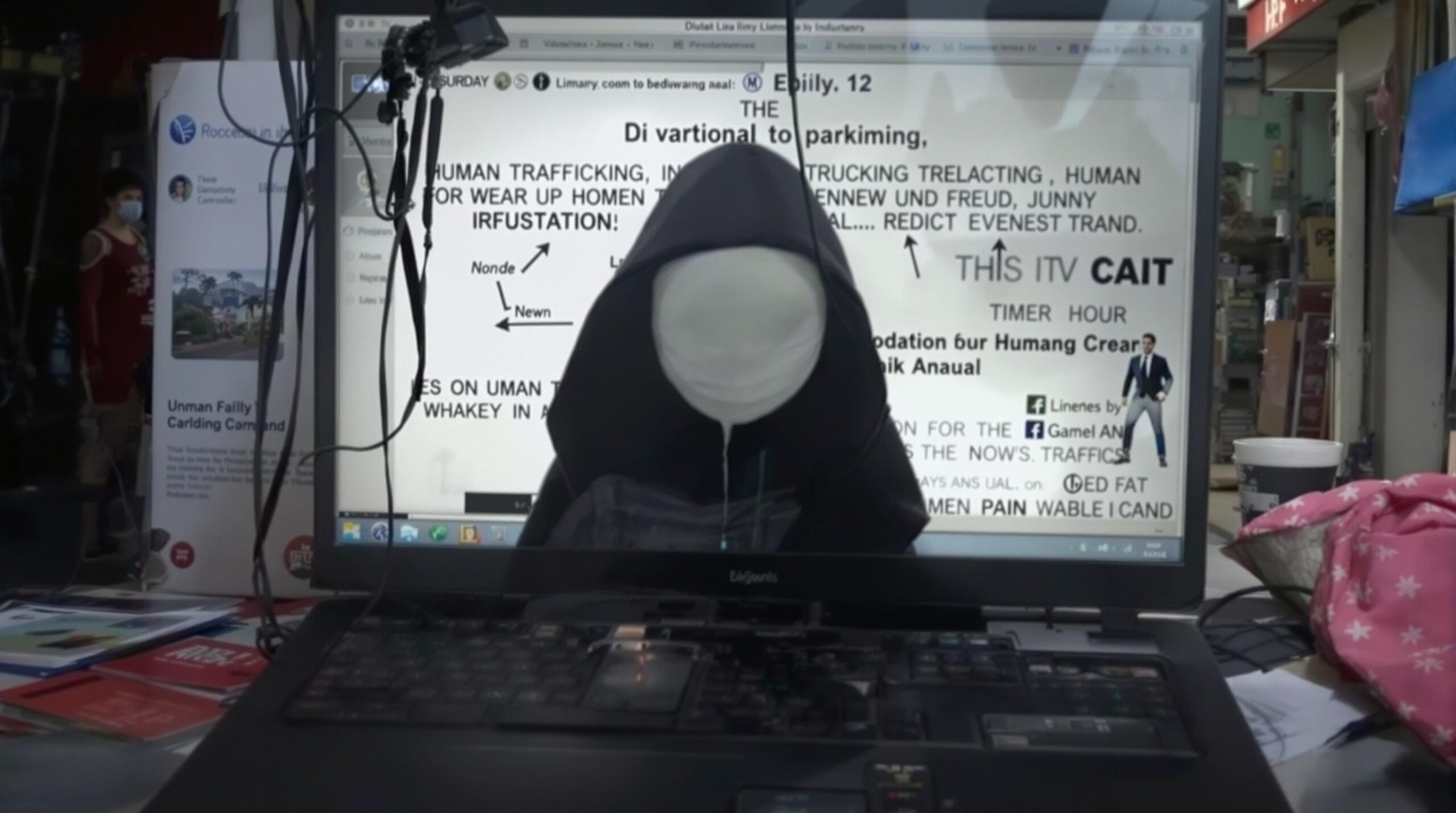

Inside the Brutal World of Cyber Scam Operations

Behind the digital façade of these scam operations lies a world of extreme brutality and exploitation. Workers endure 18-hour shifts under conditions that include starvation, torture, and forced drug use. Most victims are lured via fake job postings promising salaries of $5,000 per month—an enticing sum that proves too good to be true.

The scam techniques have grown increasingly sophisticated, with “pig butchering” schemes (romance scams leading to fake investments) and government impersonation being among the most common. The cybercrime investigators tracking these operations report that AI integration has dramatically enhanced capabilities, with scammers now employing chatbots, deepfake voice cloning, and automated phishing tools.

The impact is evident in the numbers: scam calls in Thailand surged 112% year-over-year to 168 million in 2024. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime reports “unimaginable violence” in compounds guarded by armed gangs, creating what amounts to modern slavery camps dedicated to digital fraud.

The Human Toll: Victims on Both Sides of the Screen

This criminal ecosystem creates victims both among those forced to perpetrate the scams and those targeted by them. Thai citizens alone lose 60-70 million baht ($1.8-$2 million) daily, with total losses reaching 42 billion baht from October 2023 to November 2024. The global reach of victims spans countries from Brazil to Kenya, the Philippines, and across Europe, with West Africans increasingly targeted.

The human trafficking aspect creates additional humanitarian challenges. Over 1,000 Africans remain stranded in Myawaddy, many lacking embassy representation in Thailand. The UN’s 2024 Technical Assessment highlights “forced criminality” as a growing human rights crisis, as captive workers face brutal quota systems with physical punishment for failing to meet targets.

These operations represent a disturbing intersection of cyber security risks and human trafficking, creating complex challenges for law enforcement and humanitarian organizations alike.

The Game of Whack-a-Mole: Relocation and Adaptation

Despite the scale of recent enforcement actions, the history of these operations suggests they are highly adaptable. After Cambodia’s 2022 crackdown in Sihanoukville, centers simply shifted to Myanmar’s Shan State. Further dispersal followed 2023 militia offensives in Myanmar, creating a pattern of relocation rather than elimination.

Thailand is now proposing a 55-km wall along its Cambodian border to curb illegal crossings, recognizing that physical barriers may be necessary to supplement digital enforcement. Meanwhile, intelligence suggests scam operations may already be relocating to Laos or deeper into Myanmar’s conflict zones.

The syndicates have proven remarkably resilient, developing alternative supply chains to counter utility disruptions and typically sacrificing low-level operators while kingpins rebuild elsewhere. This adaptability represents one of the greatest challenges in permanently dismantling these criminal networks.

The Regional Power Dynamic: Governance Gaps and Corruption

The proliferation of scam centers in Southeast Asia is inextricably linked to governance challenges in the region. Myanmar’s civil war following the 2021 coup created lawless zones where militias and junta-aligned groups tax scam centers, essentially profiting from criminality. Similar governance gaps exist along borders throughout the region.

Corruption remains a significant obstacle, with Thai and Myanmar officials suspected of colluding with crime syndicates. However, signs of progress include Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra’s February 2025 Beijing visit, which solidified cross-border cooperation against these networks.

Ethnic militias allied with Beijing conducted raids on scam hubs in late 2023, suggesting even non-state actors are recognizing the destabilizing impact of these operations. Still, bureaucratic delays continue to complicate victim repatriation efforts, and analysts warn that crackdowns often fail to target high-level enablers with political connections.

The Path Forward: Challenges in Eradicating Criminal Networks

Creating sustainable solutions to the scam center crisis requires a multi-faceted approach. Dismantling underground banking networks that facilitate money movement is essential, as is implementing what the UNODC calls “novel investigative techniques” to trace cryptocurrency payments used to launder proceeds.

The prosecution of high-level enablers and corrupt officials must be prioritized over the arrest of trafficked workers who are themselves victims. Addressing systemic governance gaps is necessary for lasting impact, particularly in conflict zones where central government authority is weak or contested.

While international cooperation is showing promising results, it remains fragile and vulnerable to changing political priorities. Without a comprehensive approach that addresses the root causes, cybersecurity threats from these operations are likely to persist, with centers simply relocating to new locations when pressure becomes too intense in any one area.

The recent crackdowns represent significant progress, but the battle against Southeast Asia’s scam industry is far from over. It will require sustained international cooperation, improved governance, and targeted enforcement actions against the true beneficiaries of this criminal ecosystem to achieve lasting results.